Climate science briefing by Prof Kevin Anderson: Transcript

A briefing was given by Prof Kevin Anderson, in February 2025, titled "From Rio to Paris to the UK".

It was given on Zoom to a meeting organised by Just Stop Oil and published at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=barReD6a-TA.

This is a full transcript of the main talk, but some of the slides have been omitted for reasons of space.

Chair's introductory remarks:

Kevin is Professor of Energy and Climate Change at Manchester University. I promised a short introduction, so Kevin, I will hand over to you, but just to say thank you very much for being with us.Kevin Anderson:

Yes, that's my pleasure.I should also add, as well as being an academic now, I have had a previous existence as a designer and builder of offshore oil platforms.

So I have a background in the petrochemical industry, which is very helpful as an engineer, I think, looking at some of the challenges that we face today, understanding what you can and cannot do with engineering. It's been very helpful for me in the work I'm doing.

So I've called this talk here "From Rio to Paris and then on to the UK". And the subtext here, or the subtitle is a motto from Gramsci, which I think is probably quite appropriate for many of you at this event tonight: "Pessimism of the intellect and optimism of the will". And I think any of us who are deeply involved in climate change, it's hard to be, you know, optimism of the intellect is something you can't really have because things don't look particularly good.

So I've called this talk here "From Rio to Paris and then on to the UK". And the subtext here, or the subtitle is a motto from Gramsci, which I think is probably quite appropriate for many of you at this event tonight: "Pessimism of the intellect and optimism of the will". And I think any of us who are deeply involved in climate change, it's hard to be, you know, optimism of the intellect is something you can't really have because things don't look particularly good.But the optimism comes from actually trying to drive change, actively engaging in one way or another, which many of you probably are, I'm sure. So I think it probably captures you quite well, some of you quite well, actually. So the presentation I'm going to give is just an overview of where we are from the science on climate change and what we need to do about it, how urgent it is. I think it's probably more urgent than we typically get told by the press and indeed I would argue even by many academics - they significantly sugarcoat the narrative.

So this is work based on analysis I've undertaken with my colleagues Dan Calverley and Isak Stoddard but also others in the Tyndall Centre in the UK and over here in Siemens in Sweden which is where I am at the moment.

[ 01:47 ]

So for those of you that use social media, I have an active, reasonably active Bluesky account and a slowly less active Twitter account. I only use those for work. I post quite a few things now, mostly now on Bluesky and also have a website where I post some of the work that I do.

So I'm going to start off by asking the question about what is our key concern over climate change. And for people like me, it's very easy to think about it being temperature - 1.5°C of warming or 2°C of warming. But in reality, of course, it's not those things. What we're worried about are impacts. So whether it's flooding or droughts or fires, they impact the agriculture, that might have migration and all the other aspects that all the other sort of follow-ons that come from that. So it's the impacts that are most important for us and we mustn't forget that, and probably that's more speaking to the expert community, I think we often do forget that we're focusing on impacts which are very much more sort of human issues than the temperatures themselves.

So I'm going to start off by asking the question about what is our key concern over climate change. And for people like me, it's very easy to think about it being temperature - 1.5°C of warming or 2°C of warming. But in reality, of course, it's not those things. What we're worried about are impacts. So whether it's flooding or droughts or fires, they impact the agriculture, that might have migration and all the other aspects that all the other sort of follow-ons that come from that. So it's the impacts that are most important for us and we mustn't forget that, and probably that's more speaking to the expert community, I think we often do forget that we're focusing on impacts which are very much more sort of human issues than the temperatures themselves. But it's not even just the impacts, it's actually the rate of change of impacts. If the impacts that we saw occurred over a thousand years or longer, then that would probably be okay. If they could occur in five years, then human systems and ecosystems simply can't adapt to them. So the question is then, how rapid can impacts change that we can still deal with them as human systems, as ecosystems? And temperature is just a proxy for those rates of change of impacts.

But there's another central question in all of this. I think right throughout climate change, there's a question that by and large we haven't asked appropriately in the Global North, is who is the ‘we’ that makes the choice as to what is or is not appropriate? So the ‘we’ question, I will come back to that later on in some of these slides.

So I'm going to go back right to 1992 now and ask, well, what is it we've committed to deliver? And I think often we focus on the Paris Agreement. But really what was important was what was set up in 1992 when we established the UNFCCC. And back then, there was the Rio Earth Summit. And at that summit, there were two really key parts that came out of that in relation to climate change. And they were given fancy languages, which I'm going to simplify for it here.

So I'm going to go back right to 1992 now and ask, well, what is it we've committed to deliver? And I think often we focus on the Paris Agreement. But really what was important was what was set up in 1992 when we established the UNFCCC. And back then, there was the Rio Earth Summit. And at that summit, there were two really key parts that came out of that in relation to climate change. And they were given fancy languages, which I'm going to simplify for it here. One of these is to cut emissions so as to avoid dangerous levels of climate change. And virtually every country in the world signed up to this. There were very few exceptions at all.

And the second part in Article 3, which is also very important and has been pretty much treated just with lip service ever since by the Global North, is that we would cut emissions fairly under this rubric of common differentiated responsibilities, CBDR as it's often called. But basically that means we would cut emissions to avoid dangerous levels of climate change and we would cut them fairly with developed nations, and there was a category of developed and developing nations, taking the lead.

And the second part in Article 3, which is also very important and has been pretty much treated just with lip service ever since by the Global North, is that we would cut emissions fairly under this rubric of common differentiated responsibilities, CBDR as it's often called. But basically that means we would cut emissions to avoid dangerous levels of climate change and we would cut them fairly with developed nations, and there was a category of developed and developing nations, taking the lead. It was 23 years later before we actually defined what do we mean by ‘dangerous’ - 23 years. And there we came out in the Paris Agreement with language I hope you're all familiar with to hold well below 2° centigrade and pursue no more than 1.5. And again, probably for most of you here that you're reasonably familiar with these temperatures, but these are global average temperatures compared with the pre-industrial period. So really the 1850s, round about there, before we started burning fossil fuels at any scale.

And these are huge changes in all of modern human history. We have never seen changes like this. So this is completely moving beyond anything that we have really in modern times, in modern human history, going back way before the Egyptians and so forth, have we lived through anything like the changes that we're now seeing? But we also agreed to be guided by the science, and on the basis of equity.

And every single COP, every single negotiation, every year, the big international negotiations, we sign up to this concept of common but differentiated responsibility, the basis of equity. But then it's completely ignored by the wealthy countries. In fact, if some of you may have seen the Committee on Climate Change, the Government's Committee on Climate Change, had their report out, Carbon Budget 7 reports out yesterday. And again, it pretty much just ignores the equity part within the Paris Agreement.

[ 05:54 ]

Now the problem with for us as scientists and people who play with the numbers is that Paris is in the form of adjectives. It's well below or you know, pursue. That sort of language isn't helpful for us when we're trying to get some feel of the numbers that we need to feed back into the policy process. And over time what's happened is well below 2°C, has come to mean an 83% chance of staying below 2. And that sounds very precise, but the sort of language that's used in the intergovernmental panel on climate change. But basically, it's a pretty good chance of staying below 2, but it's still nowhere near certain, which I think the language of well below 2 would mean that you shouldn't definitely not go above it. But there's still a reasonable chance here that we could exceed 2°C.

[ 06:35 ]

And the second new commitment we made at Paris was this idea of pursuing 1.5. And typically that's seen as having less level of certainty to it, probably somewhere around 50-50 chance of staying below 1.5°C. And people take slightly different views of this. But overall, that's the framing that I think is quite common now within the academic realm, but also that the EU uses these sorts of levels of change. The UK Committee on Climate Change has used the 50% figure as well for 1.5.

But that was Paris, which was back in 2015. And we've learned a lot since then. It was not far off a decade since the Paris Agreement. And there have been important sort of advances in understanding the impacts between 1.5 and 2°C. So though it sounds like not very much, it's just half a degree, there are lots of things that start to occur, particularly risks that start to get worse between 1.5 and 2, as well as some of the impacts as well. We're already witnessing these.

And if we go back to the Paris Agreement, remember, our agreement is not about 1.5 or 2. It's about avoiding dangerous levels of interference with the climate system. So it's what we consider to be dangerous. So I think it's now important to revisit the Paris Agreement. And I think this is quite common, at least, I think even in the political realm, that we now talk almost more about 1.5 than we do about 2°C. So now really, I'll say our primary commitment is about staying, no, we're going no more than 1.5°C of warming. Now, I'm saying this at the same time that we're actually hitting 1.5°C. And I'll come back to it later that I simply, I say this, again, with a very heavy heart, I don't think we can stay below 1.5 - I don't know how we would deliver on it anyway. If someone else knows I'll be keen to know. I think we will really struggle to stay below 2 but that's a choice we still have, if you like.

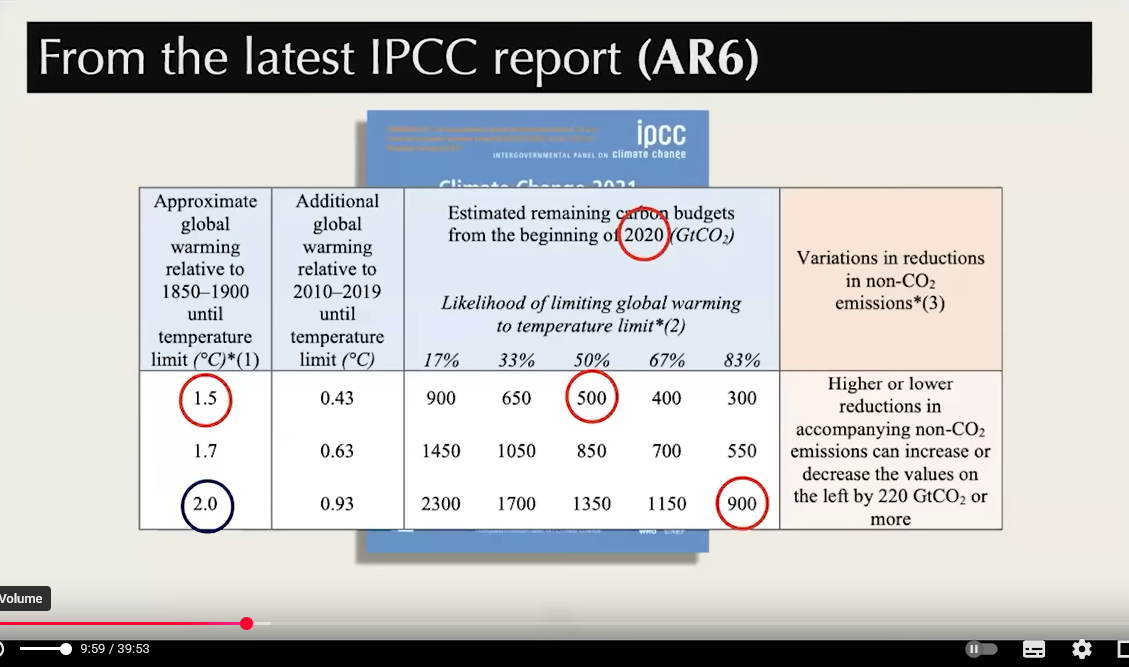

So once you've got the framing there the science can come in and start to say okay what does that look like in terms of policy framework, so those choices of 1.5 and 2°C and even the the probabilities, really they're political - science can only inform that debate - it doesn't tell you what is dangerous and what is not dangerous - that's a personal view, a political view, a cultural view, as to what is dangerous. But they're the figures that have come out now from the Paris Agreement. So we as scientists, we can now say, well, what does that mean? How do we understand the timeline for that? And in the last set of reports in the IPCC, which were now back in 2021, in those reports you've got tables like this [slide from AR6] which for those people who don't get involved with the concept of carbon budgets are a bit meaningless but they're actually quite helpful you can use these to interpret what this means in terms of policies particularly in terms of how much carbon dioxide we can emit and therefore really how many tonnes of fossil fuels we can use so these play directly into a policy framing so if you want to stay below 1.5 or 2°C these tables from 2020 and for different chances of staying below those temperatures, they give you a range of carbon budgets, that's the total amount of carbon dioxide at a global level that we put in the atmosphere if you want to stay below those temperatures or these probabilities of those temperatures.

So once you've got the framing there the science can come in and start to say okay what does that look like in terms of policy framework, so those choices of 1.5 and 2°C and even the the probabilities, really they're political - science can only inform that debate - it doesn't tell you what is dangerous and what is not dangerous - that's a personal view, a political view, a cultural view, as to what is dangerous. But they're the figures that have come out now from the Paris Agreement. So we as scientists, we can now say, well, what does that mean? How do we understand the timeline for that? And in the last set of reports in the IPCC, which were now back in 2021, in those reports you've got tables like this [slide from AR6] which for those people who don't get involved with the concept of carbon budgets are a bit meaningless but they're actually quite helpful you can use these to interpret what this means in terms of policies particularly in terms of how much carbon dioxide we can emit and therefore really how many tonnes of fossil fuels we can use so these play directly into a policy framing so if you want to stay below 1.5 or 2°C these tables from 2020 and for different chances of staying below those temperatures, they give you a range of carbon budgets, that's the total amount of carbon dioxide at a global level that we put in the atmosphere if you want to stay below those temperatures or these probabilities of those temperatures. So if you want a 50/50 chance of 1.5, then according to the IPCC, back in 2020, you could emit about 500 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide. And that probably doesn't mean too much to many of you, and I'll come back to these numbers in a minute, if you were staying below 2°C, well below 2, then you get a budget that's not far off twice as big as that, a little bit less, 900 billion tonnes.

So if you want a 50/50 chance of 1.5, then according to the IPCC, back in 2020, you could emit about 500 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide. And that probably doesn't mean too much to many of you, and I'll come back to these numbers in a minute, if you were staying below 2°C, well below 2, then you get a budget that's not far off twice as big as that, a little bit less, 900 billion tonnes.But that was 2020. Since Paris, we've emitted into the atmosphere, what, 200 or so billion tons of carbon dioxide. Sorry, since Paris, since the IPCC reports. Since Paris, we've emitted about a third of a trillion tons of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Every year, we're putting 41, 42 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. And that's building up year on year. So I think it is time now in 2025 that we revisit the science that fed into the IPCC. And it's the same scientists that are doing this work. And if you look at some of the papers that are out recently, we've got an improved understanding of a number of factors. Probably most important of these is aerosols. So as we clean up fossil fuels, and in theory, then as we stop using them, that's not happening yet, but as we stop using them, but as we clean them up, we're getting less aerosols in the atmosphere. And the aerosols in the atmosphere actually have been acting like a cooling blanket. So they've been reflecting some of the heat. So the heat that we've generated from more carbon dioxide has to some degree been compensated by the aerosols. And we're getting a much better understanding of that. And a number of other factors here, we're getting improved understanding since the last IPCC report. So I think it's really important for us to revisit the science and what does that tell us?

The choice of which carbon budgets are used, because there are a few budgets out there. I think there is a responsibility of us as sort of cogent users of these things to think about about those budgets. So first question would be, if we're looking at other papers, academic papers and assessments, are they for not exceeding or staying below 1.5 or 2°C? Or indeed, are they the amount of carbon dioxide you can emit as you go through those temperatures to higher temperatures? And you'd be quite careful because quite a few papers do exactly that.

So it looks like, oh, you can emit a lot more carbon dioxide, but that's because they're going through those temperatures to higher temperatures, often with some belief that our children will find ways to bring the temperature back down to 1.5 or 2. So in my view, those sorts of things can be deeply misleading.

[ 12:00 ]

What probabilities are being assumed? So you have to be quite careful about that because some papers, there's a paper out recently and it was easy to think it was using either a 50/50 chance or an 83% chance, but it was using a 67% chance, I think, of staying below the temperature. So that changes again the size of the budget, the amount of fossil fuels you can burn.

Are they taking account of the latest understanding of aerosols? Are they embedding other feedbacks? Now, some of them can't embed all the feedback, so then feedbacks aren't sufficiently well quantified to put in the models. But overall, I think there's a risk and consequences issue here because we're aware that most feedbacks tend to make the situation worse. So when we look at the budgets that are there, we really still think we should see them as probably conservative. And that's important from a policy perspective because that tells us something about whether we want to take the risks of some of the impacts or whether in fact we should err on the side of caution and make even greater levels of reductions.

[ 13:00 ]

The budgets I've preferred come out of one of the major contributors here. So these are sort of fairly orthodox academics here, from Robin Lamboll and his colleagues, and I'm using their budgets for 1.5 and 2°C, which I would judge are probably the most scientifically up to date and carefully thought through.

[ 13:17 ]

So now I'm going to update the numbers from Paris to the start of this year, to January 2025, for 2°C and 1.5°C. The budgets we have now, and I'll put these numbers in context in a minute, the budgets we have now for 1.5 are about 170 billion tons and about 570 billion tons for 2°C. Now, if we start to look at what we're currently emitting, to stay 50% chance of 1.5, at the moment that's four years of current emissions - four years - and emissions are still going up not coming down - just four years - and even for 2°C with a whole set of additional impacts and risks associated with it so definitely heading to very dangerous territory - that's just 14 years of current emissions.

If you were to bring the emissions down at the same rate every year, you'd be looking at 19 to 20% reductions for 1.5°C. And a report that came out from the Met Office, the UK Met Office, just about, well, maybe it was five weeks ago, four or five weeks ago now, from Richard Betts in the Met Office, had the same sort of number, 20% per annum reductions now for 1.5. But even for 2°C, we're talking about 7% per annum reductions globally.

During Covid, the most intense year of Covid, we had a reduction of 5.3%. So you're almost 2 percentage points more than we had during Covid. If alternatively, rather than having it at the same level every year, you just drew a straight line from today, from January this year, down to zero, zero emissions, for 1.5 we'd have to be zero emissions by the end of 2032, and for 2°C by the end of 2052.

[ 15:00 ]

Another way to look at this, and for me I find this probably well it's been helpful to realize how rapidly we're going through the budget, for 1.5 we're going through the carbon budget at 2% every single month - so just since the beginning of this year, we're heading towards 3 - 4% of the budget for 1.5 the global budget has gone [at Feb 2025] and even for 2°C at 0.6% every single month - so when we talk about, as the Committee on Climate Change has done, 2040 and 2050, these these are just deeply misleading relative to what just some science and some maths are telling us about the scale of the challenge that we face. I've greyed out now 1.5 because in my view it simply isn't viable and I'm happy if someone else can show us how we can deliver on that, but I can't see it now possible and I'm saying that with a very heavy heart, because we know that means that lots of other people would be impacted by climate change. They've already been impacted in the Global South, and as I repeatedly say, they have often, well, typically they're people who are not part of the problem. They're very low emitters. They're a long way from here. Very little influence in the political landscape. And they're typically people of colour. And we've known this for a long time. And to be brutally honest, those of us who are framing the debate, in some respects, have been prepared to sacrifice these communities.

[16:00 ]

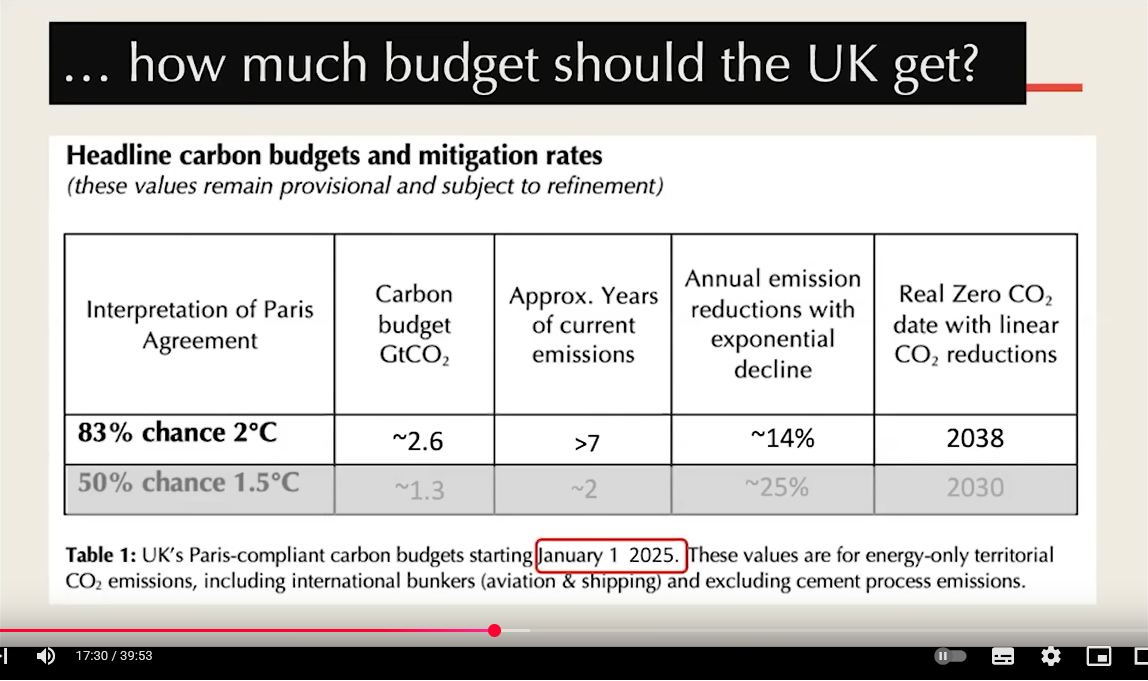

So, now I want to bring this down to us within somewhere like the UK, because we also signed up to make changes on the basis of equity. So if we think of the carbon budget and then split it between the developed and developing countries, which unfortunately is still the language that's used in all the agreements, we're just splitting the world into two parts. About 18% of the world's population, I think, live in the developed countries.

You can then ask the question of the developed countries, how much should Britain get or Sweden or the US? And this is based on some work that I did in the paper with some colleagues. I've just published them in 2021, I think it was.

So now I've taken it from the global budget and downscaled it to the UK. I've greyed out again the 1.5 because I simply don't think it's achievable. And now if you put the numbers in for the UK, take an account of equity. So we've got a weak interpretation of equity here. So it's nothing like fair, but it's the best that we could achieve, given that you can't eliminate all emissions from the Global North immediately. But we would say you've got about 7 years of current emissions in the UK if they were staying as current. But of course, if they come down, That's a reduction rate of about 14% every single year. Or if you draw a straight line, somewhere at about zero emissions by 2038 - zero emissions. If you compare this with the Committee on Climate Change's report from yesterday or the day before, I mean, this just doesn't fit. And they claim theirs aligns with 1.5, which is just... well, I think it's absolutely impossible to align the two without lots of behind-the-scenes sort of fudges, if you like.

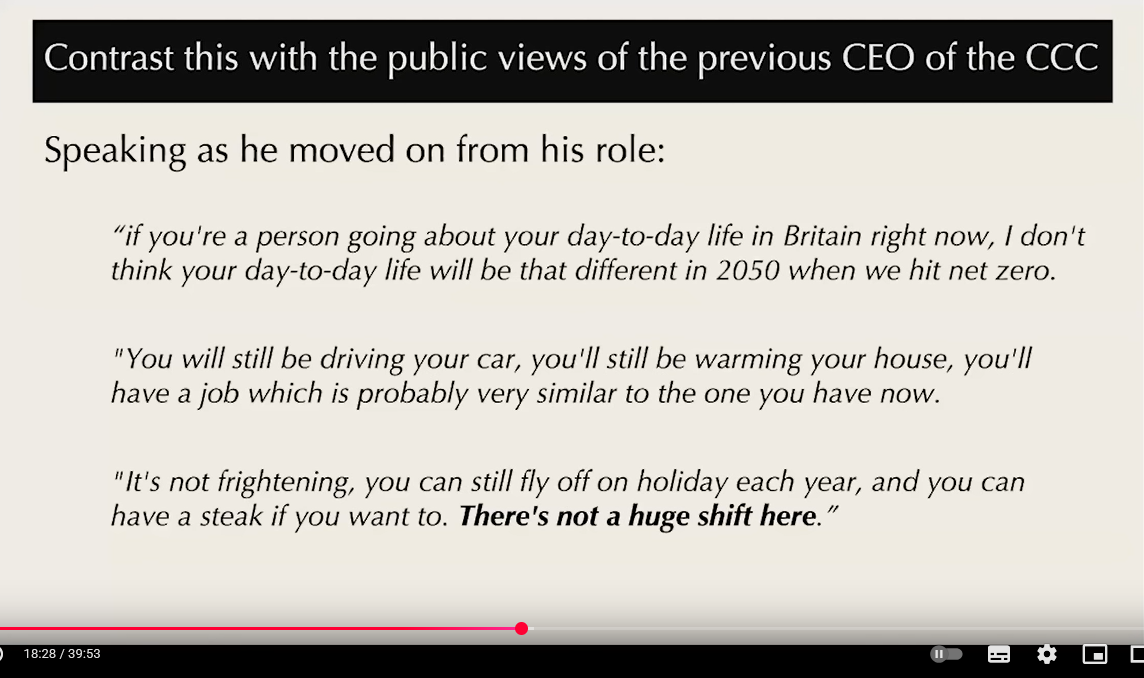

So now I've taken it from the global budget and downscaled it to the UK. I've greyed out again the 1.5 because I simply don't think it's achievable. And now if you put the numbers in for the UK, take an account of equity. So we've got a weak interpretation of equity here. So it's nothing like fair, but it's the best that we could achieve, given that you can't eliminate all emissions from the Global North immediately. But we would say you've got about 7 years of current emissions in the UK if they were staying as current. But of course, if they come down, That's a reduction rate of about 14% every single year. Or if you draw a straight line, somewhere at about zero emissions by 2038 - zero emissions. If you compare this with the Committee on Climate Change's report from yesterday or the day before, I mean, this just doesn't fit. And they claim theirs aligns with 1.5, which is just... well, I think it's absolutely impossible to align the two without lots of behind-the-scenes sort of fudges, if you like. I want to contrast those numbers with a statement from the previous head of the Committee on Climate Change. And I always refer to it as the Government's Committee on Climate Change. It's not independent. It's paid by the government to give advice to government. And it was set up by the government, or Parliament anyway. So it's not really an independent committee. But the last CEO who went on to become a Miliband advisor said, just as he left, he made this comment in relation to climate change, in relation to the CCC's view on 1.5: "If you're a person going about your day-to-day life in Britain right now, I don't think your day-to-day life will be that different in 2050 when we hit Net Zero. You'll still be driving a car. You'll still be warming your house. You'll have a job, which is probably very similar to the one you have now. It's not frightening. You can still fly off on holiday each year. You can still have a steak if you want to. There's not a huge shift here."

I want to contrast those numbers with a statement from the previous head of the Committee on Climate Change. And I always refer to it as the Government's Committee on Climate Change. It's not independent. It's paid by the government to give advice to government. And it was set up by the government, or Parliament anyway. So it's not really an independent committee. But the last CEO who went on to become a Miliband advisor said, just as he left, he made this comment in relation to climate change, in relation to the CCC's view on 1.5: "If you're a person going about your day-to-day life in Britain right now, I don't think your day-to-day life will be that different in 2050 when we hit Net Zero. You'll still be driving a car. You'll still be warming your house. You'll have a job, which is probably very similar to the one you have now. It's not frightening. You can still fly off on holiday each year. You can still have a steak if you want to. There's not a huge shift here."I have absolutely no idea how you could align that with the 1.5°C framing, 20% per annum reductions year on year at a global level. I just absolutely have no idea how you can align the two. Even for 2°C, I don't think that's in any way viable.

[ 18:49 ]

But the language you get, I hear the language in Sweden, I hear the language in France and Denmark, every country says this, every country is a leader on climate change. So we hear that sort of language in the UK. The UK is the first major economy to halve emissions between 1990 and 2022. But if you add in international aviation and shipping, if you add in trade i.e. imports and exports, then the reduction for the UK is about 20%, which is still better than Sweden, which is probably somewhere about 15%. If you look at Ireland, it's gone up actually a little bit since 1990. So, the UK is just not as bad as some of the others. But it's still only about 0.6% per annum reduction each year. Remember, we need about 14% for 2°C. But as I say, it's not as if the UK is doing any worse than some of the other so-called climate-progressive countries. There are no climate-progressive countries in the Global North.

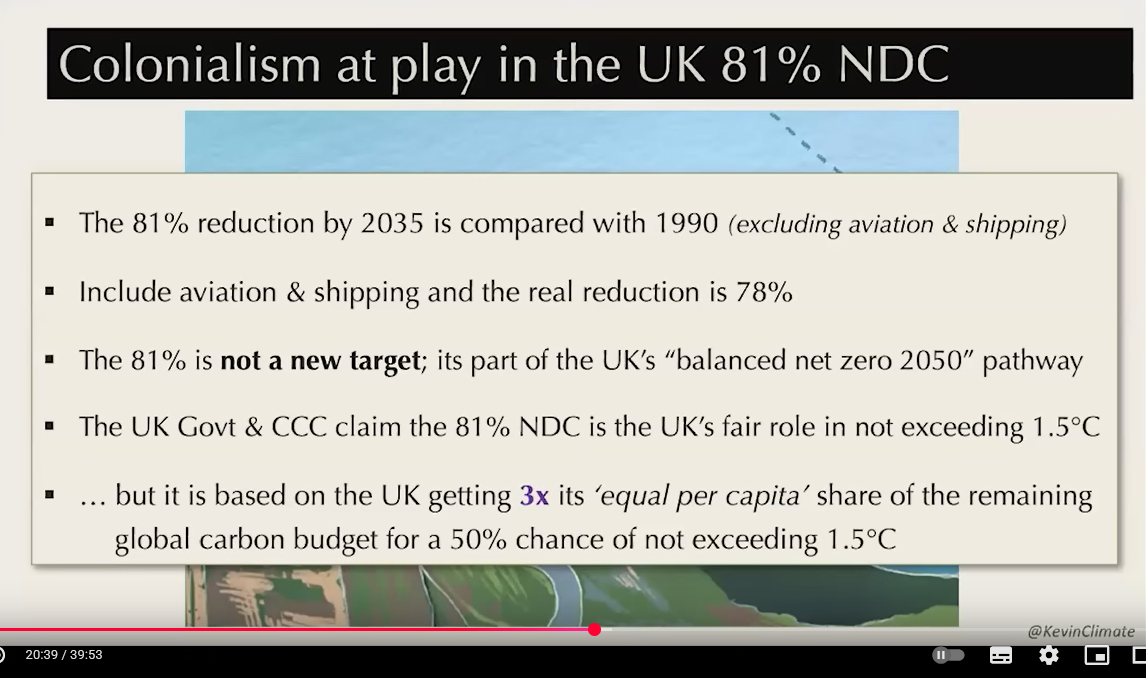

But the language you get, I hear the language in Sweden, I hear the language in France and Denmark, every country says this, every country is a leader on climate change. So we hear that sort of language in the UK. The UK is the first major economy to halve emissions between 1990 and 2022. But if you add in international aviation and shipping, if you add in trade i.e. imports and exports, then the reduction for the UK is about 20%, which is still better than Sweden, which is probably somewhere about 15%. If you look at Ireland, it's gone up actually a little bit since 1990. So, the UK is just not as bad as some of the others. But it's still only about 0.6% per annum reduction each year. Remember, we need about 14% for 2°C. But as I say, it's not as if the UK is doing any worse than some of the other so-called climate-progressive countries. There are no climate-progressive countries in the Global North.And I want to also make a comment on the NDC, the big promise, the pledge that was made during the last COP. Some of you, hopefully you heard about in the press, it was very widely covered as "The UK demonstrating leadership". And I would argue it's colonialism at play yet again.

That 81% is by 2035, compared to 1990, excludes aviation and shipping. And as the Committee on Climate Change rightly point out, it's about 77-78% reduction if you do include aviation and shipping. But it's not a new target. It was put across as some new target. That target's effectively been there for pretty much five years or so now. So there's nothing new about that target.

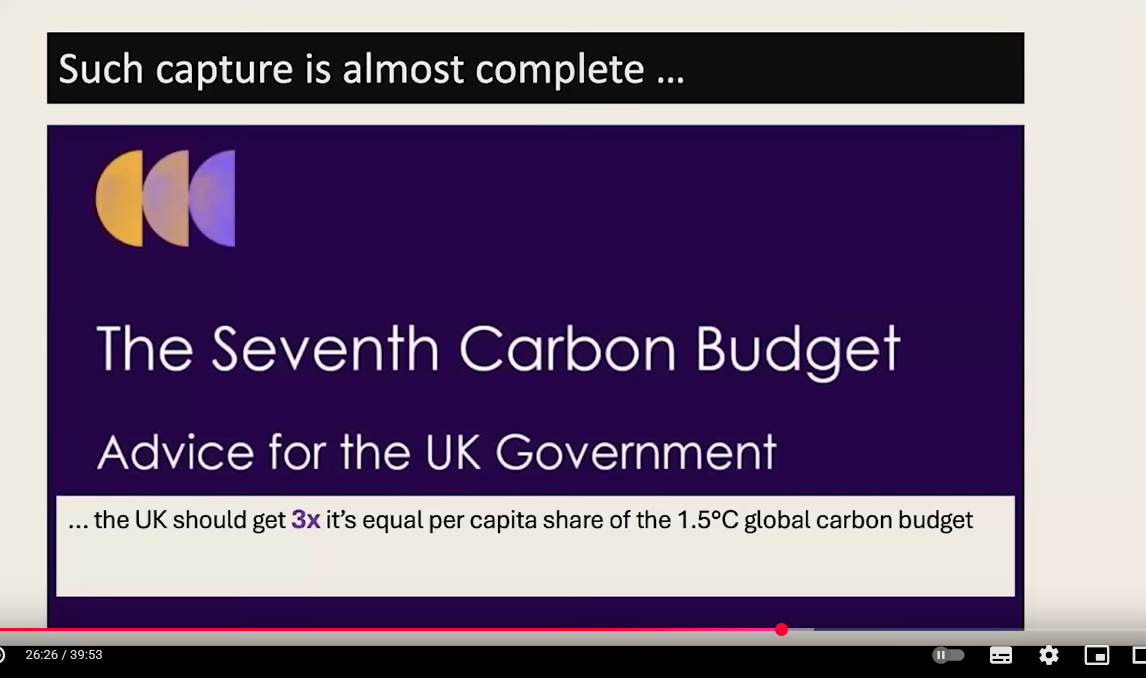

That 81% is by 2035, compared to 1990, excludes aviation and shipping. And as the Committee on Climate Change rightly point out, it's about 77-78% reduction if you do include aviation and shipping. But it's not a new target. It was put across as some new target. That target's effectively been there for pretty much five years or so now. So there's nothing new about that target.The Government and the Committee on Climate Change claim it's the UK's fair contribution to not exceeding 1.5 at roughly a 50/50 probability. But if you look at the total amount of emissions that are embedded in the pathway of which that 81% comes from, that emission pathway, this is taken directly from the spreadsheets of the Committee on Climate Change.

It assumes the UK gets about three times more emissions per person than the global average - three times more. Why should the UK get three times more than the global average? Just again, it's a sort of a colonial view that somehow we should get more. And I think I can understand a government doing that. I don't expect the academic community, the expert community to be falling for this. But I heard no criticism of this from anyone. No experts I heard speak out about this.

Why is all this so different to net zero? I'm just going to touch on this very quickly because we hear this net zero 2050 framing which in my view is incredibly dangerous. It's an expedient sort of accountancy framework which, because it's lots of numbers, it masquerades as science, but basically we're moving things between cells on a spreadsheet, between different gases over different time frames with different levels of risk. And I'm not going to go into details, but it does allow us to basically scam the system. And that's what we've done with Net Zero 2050, not just here, at a global level. The big models have done exactly the same thing here.

[ 21:42 ]

It also allows us to maintain a deeply colonial framing of climate change with this unfairness between the Global North and the Global South. And I'm not gonna say anything about that in any depth today, but there's some great work now coming out from a number of Indian scholars that have been unpicking the models that are all developed in the Global North and how they are all deeply colonial. They all assume the Global North will remain much wealthier than the Global South. In fact, I don't think any of them show any reduction in inequality. Some show an increase in inequality between the Global North and the Global South. They're also deeply reliant on negative emission technologies and carbon dioxide removal, whereby our children are expected to deploy at huge planetary scale technology that barely exists today. I mean, they're just in a few very small pilot schemes or the imagination of a few professors in universities that we're going to suck hundreds of billions of tonnes of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. Now, virtually every model does this, embeds this in it because we don't want the political repercussions of not relying on this are too severe. And the Committee on Climate Change has fallen for this as well.

It also, I think, helps us when we look at Net zero 2050. Fraudulantly, it makes us not consider the deep inequalities in our own society within countries where most emissions are not those from the average. Most emissions are driven by the relatively wealthy of us, a sizeable minority of us. And most of those emissions are discretionary, whereas for other people in society, the emissions are actually locked in structurally. This is true every IPCC scenario and the UK's balanced Net Zero pathway.

Some argue that the real strength of Net Zero is actually it brings us all together. But to me, this is where it's incredibly weak. It brings together all of these [slide]. Every one of these organizations has a Net Zero 2050 framing. But then and they're all looking for more oil and gas. Of course, they have no intention to be Net zero to be zero emissions. Equinox using wind power to get the oil out of the gas in Norway and then claiming is green oil.

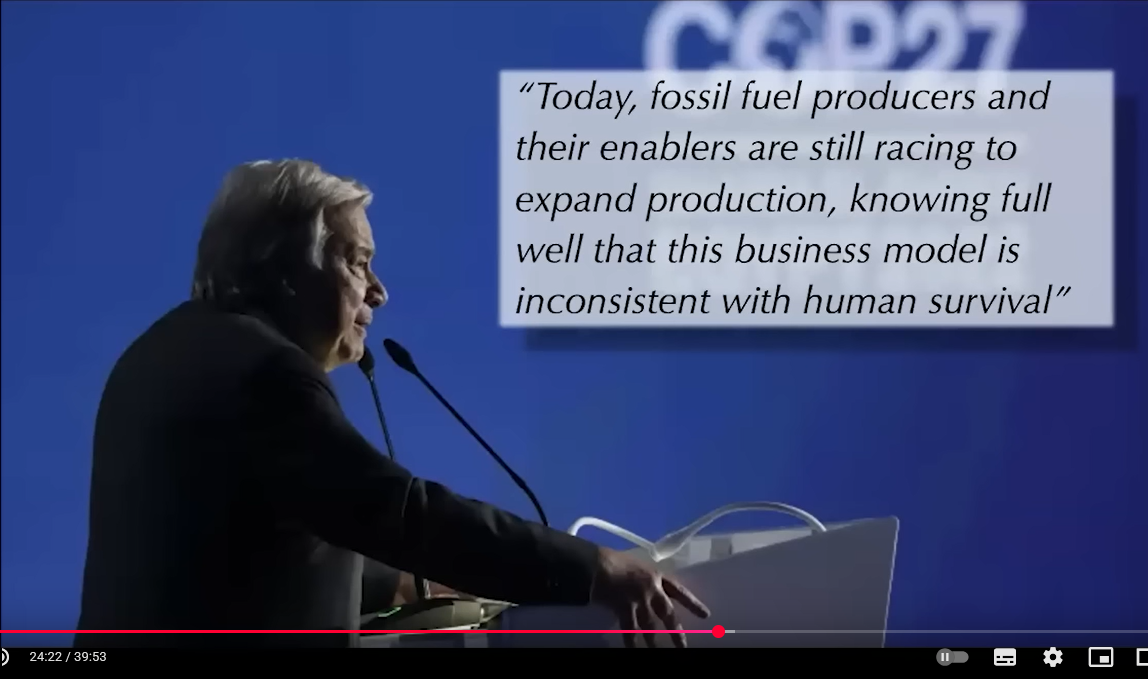

But then so is every one of these countries looking for more oil and gas. They've all got net zero or something approaching to it - China's slightly different on that. And because of the UK, we don't know what's happened. The government hasn't just said no to Rosebank, which is exactly what it should have done. Equinor pushing really hard and other people in the government pushing hard for a Rosebank field, along with airport expansion and more roads and so forth. Unusually, I think here, this is Guterres, the head of [the UN] - he’s made these comments [ slide from the UN's position and it's been very outspoken here

And he's done this in a number of issues, but particularly here, I'm just focusing on his climate change comments: "Today, fossil fuel producers [and that, of course, includes a lot of countries, as well as the companies] and their enablers are still racing to expand production, knowing full well that this business model is inconsistent with human survival". He's not saying everyone on the planet will be dead, but certainly the way that we imagine the world, the way we have the world today, it will be completely incompatible with us continuing to produce and consume more fossil fuels.

And he's done this in a number of issues, but particularly here, I'm just focusing on his climate change comments: "Today, fossil fuel producers [and that, of course, includes a lot of countries, as well as the companies] and their enablers are still racing to expand production, knowing full well that this business model is inconsistent with human survival". He's not saying everyone on the planet will be dead, but certainly the way that we imagine the world, the way we have the world today, it will be completely incompatible with us continuing to produce and consume more fossil fuels.I'm going to give a little quote here - I'm coming towards the end now - from Frederick Bastiat, who was a contemporary of Adam Smith, so quite a right-wing economist, but I think what he said then was really accurate. "When plunder becomes a way of life for a group of men [and women] in a society, over the course of time, they create for themselves a legal system that authorises it and a moral code that glorifies it." And I think that's exactly what we see here in the UK and indeed many other parts in the Global North.

But I would also add to that now, it also, through its funding and the fear of academics, it's also got now an academia that justifies it and the media, mainstream media, that disseminates it. So I think we've gotten to a point where capture is almost complete, that we've developed scenarios that look like we're still doing 1.5 and 2°C. Yet anyone who is slightly involved in climate change knows that this is just lies, fluff and nonsense. That's not what we're doing at all. I go back to the quote earlier from the previous CEO of the Committee on Climate Change, completely incompatible with our climate change commitments, or the Seventh Carbon Budget Report from the Government.

It's still got lots and lots of carbon dioxide right out to the middle of the century. Even in the middle of the century, it's got more emissions per person in the UK in the middle of the century than Kenya emits today per person.

It's got a carbon budget, which is three times what the equal per capita share would be if you were to spread out the 1.5° carbon budget around the world. And that, again, wouldn't be fair. That wouldn't be us abiding by our common differentiated responsibility. It's [unclear] either fairly allocated out of the budget.

It's got a carbon budget, which is three times what the equal per capita share would be if you were to spread out the 1.5° carbon budget around the world. And that, again, wouldn't be fair. That wouldn't be us abiding by our common differentiated responsibility. It's [unclear] either fairly allocated out of the budget. Colonialism is absolutely alive and thriving in the climate realm and very, very seldom is getting called out, including by the expert community.

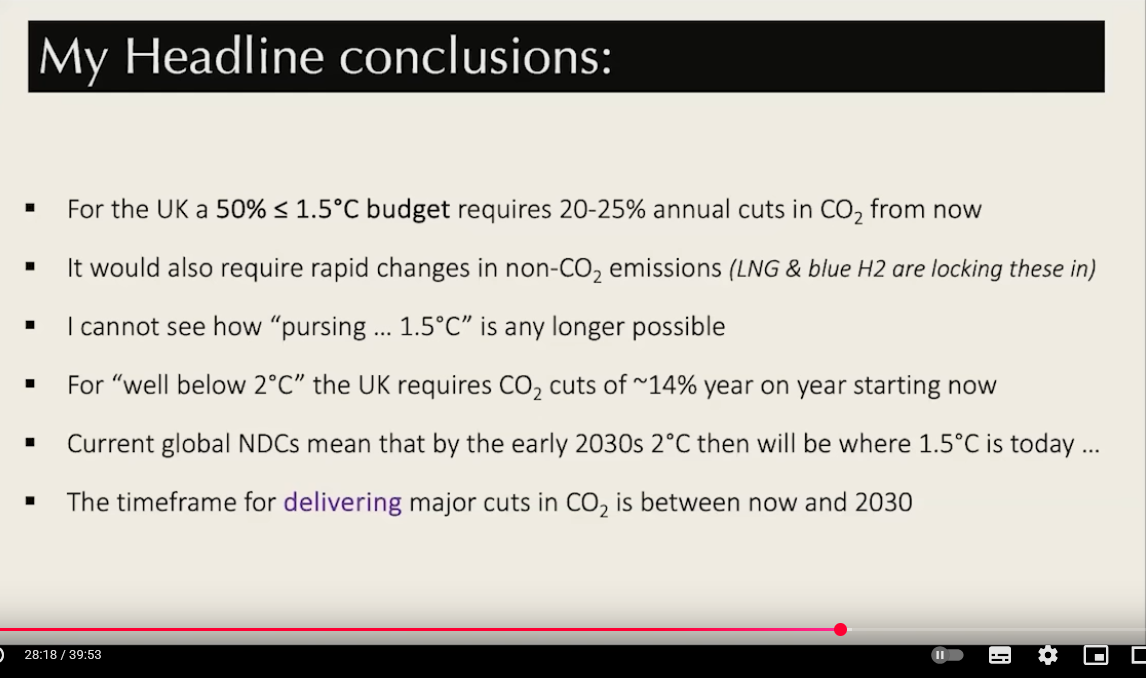

So my headline conclusions are that for a 50/50 chance of 1.5, that carbon budget, that now requires something between 20% and 25% annual cuts in CO2 every single year, 20% at a global level.

So my headline conclusions are that for a 50/50 chance of 1.5, that carbon budget, that now requires something between 20% and 25% annual cuts in CO2 every single year, 20% at a global level. If the UK had any fairness in that, it'd be even higher.

It would also require deep and rapid changes in non-CO2 emissions, and which begs fundamental questions about how the Government is stuffing the future full of liquefied natural gas and so-called blue hydrogen, all these things which are locking in ongoing and very high levels of non-CO2 emissions. I say now that in 2025, I don't know how we could deliver on 1.5. I don't think it's any longer possible.

2°C would require, if you had any fairness in there, 14% per annum cuts year on year. If you do equal per capita for the UK, [unclear: ] it still be like 7% or 8% every single year.

The current promises that we've made globally mean that by the early 2030s, which is no time from now, the 2°C framework to deliver on that will be as challenging as the 1.5 is today, which I would argue, and so would many other people, is not achievable. So literally in a handful of years from today, 2°C will be as impossible as 1.5 is now.

So the real time for delivery is not 2040, the Committee on Climate Change talk about, or 2050 that lots of other people talk about. The real timeframe delivery is this evening and tomorrow and next week and the year after that. It's between now and 2030. And I've highlighted there, it's about delivering cuts, not setting in train the cuts to occur after 2030. That literally is too late for 1.5, well, for 2°C. We're talking about delivering the cuts between now and then.

So I come back to that opening quote from Graham Gramsci, "Pessimism of the intellect and optimism of the will." There's nothing in the numbers that I've displayed tonight that gives us any sense of hope from looking at the analysis. The hope only resides in our trying to drive change. There are still things that we can do to try to change. I don't see how they work for 1.5, but I think 2°C is still there.

The business as usual model, the framework we have today, the acquiescence and complicity of a lot of the experts in this and staying quiet are a real problem here.

And perhaps that's where the optimism of the will part comes back to the people that are engaged in your event this evening, that you're the ones that will have to drive, to some degree, drive those of us who know more about the subject to be more honest and direct about the challenges that we face. And on that note, thank you very much for listening.

Other communications from the same academic institution

Anderson et al (2025) The UK’s year of climate U-turns exposes a deeper failurehttps://theconversation.com/the-uks-year-of-climate-u-turns-exposes-a-deeper-failure-254499

Started: 18 Aug 2025

✖

✖